3.

Results

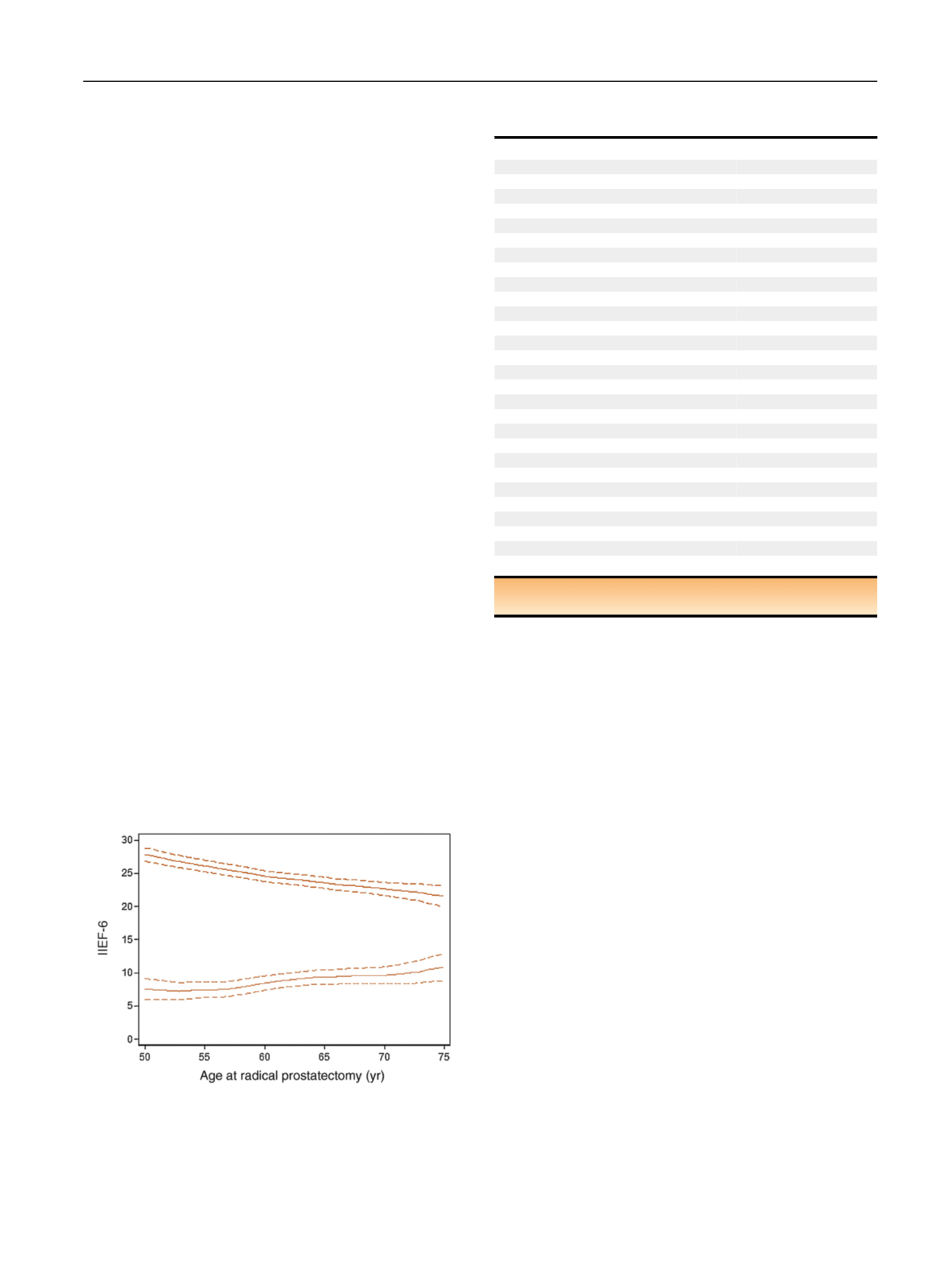

Table 1summarizes the clinicopathologic characteristics of

the study cohort from which patient-reported data were

obtained. Median patient age in this cohort was 62

(interquartile range: 57- 67) yr, with a median reported

baseline IIEF-6 score of 28 (interquartile range: 21

–

30).

Each year increase in patient age resulted in a

[10_TD$DIFF]

0.27 (95%

CI:

[16_TD$DIFF]

0.18,

[17_TD$DIFF]

0.36,

p

<

0.0001) point reduction in baseline IIEF

scores

( Fig. 1). Comorbidity reduced baseline scores, with a

[18_TD

$DIFF]

0.81 (95% CI

[19_TD$DIFF]

2.01,

[20_TD$DIFF]

0.38;

p

=

[21_TD$DIFF]

0.2),

[22_TD$DIFF]

3.02 (95% CI

[23_TD$DIFF]

4.40,

[24_TD$DIFF]

1.65;

p

<

0.0001), and

[25_TD$DIFF]

3.77 (95% CI

[26_TD$DIFF]

5.58,

[27_TD$DIFF]

1.96;

p

<

0.0001) point change in IIEF for one, two, or three or

more comorbidities. However, there was no evidence that

erectile function declined faster with increasing age in

patients with comorbidities (

p

=

[28_TD$DIFF]

0.16 for the interaction

term). As such, comorbidities were excluded from the

model estimating postoperative recovery.

The degree of erectile function recovery after RP also

decreases (

[11_TD$DIFF]

0.16

[12_TD$DIFF]

IIF points/yr, 95% CI

[13_TD$DIFF]

0.27,

[14_TD$DIFF]

0.05,

p

=

[15_TD$DIFF]

0.006). For example, a typical 55-yr-old patient would lose

7.5 points from pre-RP to 12-mo post-RP; a 60-yr-old

patient who would lose 8.4 points

( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 2illustrates the predicted erectile function scores

over time for a 55-yr-old patient with a baseline IIEF-6 score

of 26 with immediate versus surgery delayed by 5 yr, a

timepoint at which about a third of men initially managed

on active surveillance have been treated

[2] .The average 10-

yr IIEF score was higher on delayed surgery (2.1 points, 95%

CI: 0.4, 3.9). Indeed, even if we assume a very short delay to

surgery of only 3 yr, we continue to see a significant

improvement compared with immediate treatment

(1.5 points, 95% CI: 0.2, 3.0).

We repeated these analyses for men aged 60 yr and 65 yr

looking over 10-yr and 15-yr timeframes with similar

results

( Table 2). For example, a man diagnosed with

prostate cancer at 65 yr old would have an average of

3.3 more points on the IIEF-6 over a 10-yr period if RP were

delayed for 5 yr (95% CI: 1.8, 4.6). In each scenario, delayed

RP was estimated to lead to an increase inmean IIEF-6 score,

although differences between groups were not statistically

significant in all cases.

As erectile function was superior on active surveillance

even if a man was subject to surgery after a relatively short

duration, incorporation of longer delays to surgery, or no

surgery at all, would have no effect on our conclusion that

erectile function is superior on delayed surgery. According-

ly, these planned analyses were not conducted.

4.

Discussion

Using a robust database of baseline and postoperative

patient reported outcomes for men with low- and

intermediate-risk prostate cancer, we found that the

predicted average long-term erectile function is higher

for men who undergo delayed compared with immediate

RP at a younger age. Our findings disconfirm the hypothesis

that early surgery compared with active surveillance

improves sexual function by utilizing a window of

opportunity for postoperative recovery. Indeed, the results

suggest that a man should opt for active surveillance even if

he knew that surgery would be required within a few years.

Our data can be compared with other reports in the

literature. First, there is clear evidence for our finding that

recovery is age-related. Brajtbord et al

[7]report erectile

recovery after RP in two age groups,

60 yr and

>

60 yr.

Older men were more likely to have a

“

clinically significant

”

Table 1

–

Clinicopathologic characteristics of cohort (

n

= 1103; data

are given as median and quartiles or frequency and percentage)

Age (yr)

62 (57, 67)

Preoperative IIEF-6

28 (21, 30)

Preoperative PSA (ng/ml)

4.9 (3.6, 6.5)

Biopsy cores (

N

=

[5_TD$DIFF]

1095)

12 (6, 13)

Positive biopsy cores (

N

=

[6_TD$DIFF]

1099)

3 (1, 5)

Biopsy Gleason grade group

1

566 (51%)

2

537 (49%)

RP Gleason

[7_TD$DIFF]

grade group

1

264 (22%)

2

681 (62%)

3

153 (14%)

4

13 (1.2%)

5

12 (1.1%)

T Stage

pT2c

810 (73%)

pT3a

259 (23%)

pT3b

34 (3.1%)

Positive surgical margins

151 (14%)

Unknown

1 (

<

0.1%)

Comorbidities

0

372 (34%)

1

390 (35%)

2

234 (21%)

3+

107 (10%)

Type of surgery

Laproscopic

288 (26%)

Open

294 (27%)

Robotically-assisted laproscopic

521 (47%)

IIEF-6 = International Index of Erectile Function-6; PSA = prostate-speci

fi

c

antigen.

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1

–

Effects of age on erectile function and recovery of erectile

function after radical prostatectomy. Black line

[3_TD$DIFF]

: International Index of

Erectile Function-6 (IIEF-6) measured erectile function by age. Grey line

[4_TD$DIFF]

:

loss in IIEF-6 measured erectile function from pre- to 12-mo postradical

prostatectomy by age. Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals. Older

patients have lower baseline IIEF scores and experience larger losses in

erectile function compared to younger patients after surgery.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O GY 7 3 ( 2 0 18 ) 3 3

–

3 7

35