decrease in sexual outcomes, particularly bother. In a paper

describing a prediction model for postoperative erectile

dysfunction

[2_TD$DIFF]

, Alemozaffar et al

[5]reported that increasing

age was associated with a decreased probability of erectile

function, even after adjusting for baseline function. The

time course of erectile function we report can be compared

with data from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study

[8] .Results are similar except that erectile function recovery

appears better in the current study, possibly due to the

differences between specialist and community settings.

Poorer recovery overall would push our results even further

in favor of delayed surgery.

Donovan et al

[6]report erectile function over a 6-yr

period in the ProtecT randomized trial comparing surgery

with active surveillance. Men in the surveillance groupwere

subject to treatment on progression

—

with approximately

35% being treated by 6 yr

[9]—

and hence the outcome

reported includes declines associated both with aging and

with treatment. Erectile function was superior in the active

surveillance arm compared with surgery, supporting our

principal findings. The other major randomized trial that

compares surgery with conservative management is SPGC4.

The authors report rates of erectile dysfunction of 66%

versus 24% and 81% versus 75% at 4 yr and 12 yr, respectively

[10] .While this lends general support to our findings, SPCG4

is not directly relevant to current practice as patients in the

conservative management group were not as aggressively

followed as would be typical for contemporary active

surveillance approaches. As such, the rate of treatment was

lower

—

less than 20% at 10 yr

—

leading to lower rates of

treatment-related erectile dysfunction.

The advantage of using a modeling approached based on

empirical data compared with studies, such as ProtecT,

based on empirical data alone, is our ability to model

follow-up over a 10

–

15-yr period. That said, modeling

approaches do have limitations. One major assumption we

make is that cross-sectional data on preoperative function

by age can be used to estimate how erectile function would

change over time on an active surveillance program. As

there is no strong evidence that aspects of active surveil-

lance such as repeat biopsy

[11,12]have a strong effect on

erectile function, age-related declines seem the most

reasonable hypothesis.

Due to limited data on long-term recovery by age, we

assume that recovery is complete by 2 yr, even though there

is evidence that erectile function continues to recover in

some men after this time point

[13]. This type of

underestimation of recovery would constitute a bias against

immediate surgery. However, we do not incorporate

discounting, the principle that having something now is

more valuable than having it later. One recommended rate

of discounting for health outcomes is 1.5

–

2%

[14], equiva-

lent to 14

–

18% over 10 yr. The theory behind immediate

surgery is that although a patient will suffer short-term

morbidity, long-term recovery will be superior. Failure to

incorporate discounting is therefore a bias towards

immediate surgery. Our best guess is that these two

biases

—

longer-term recovery and discounting

—

are approx-

imately equal and so would not have a large effect on our

conclusions.

We also assume that IIEF is linearly associated with

erectile function, that is, a given change in IIEF is equally

important to a man at all levels of IIEF. This is unlikely to be

true as, say, a difference between an IIEF of 5 versus 8 has no

impact on a man

’

s sex life, whereas a difference between

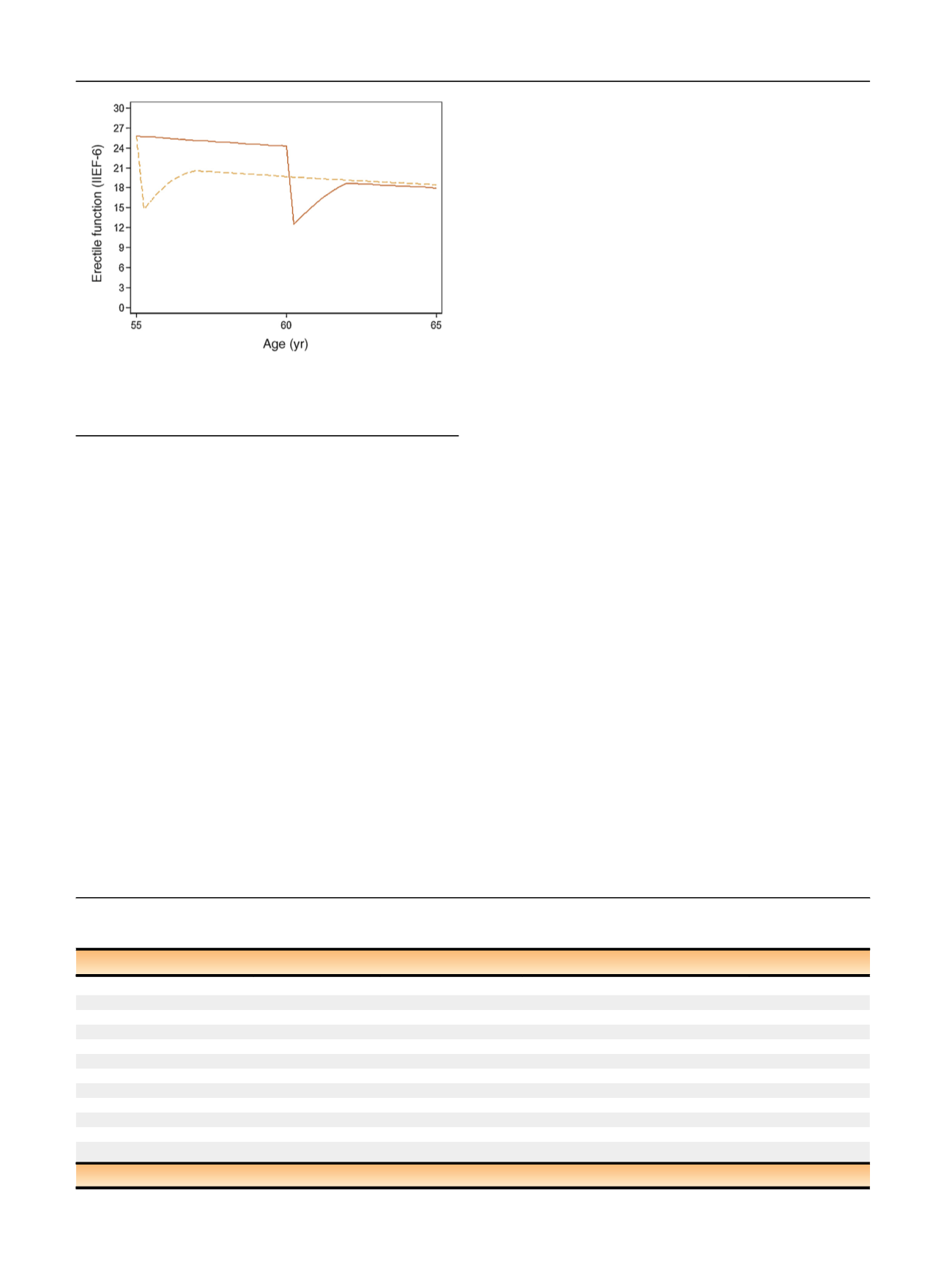

[(Fig._2)TD$FIG]

Fig. 2

–

Erectile function scores over time for a 55-yr-old patient with

a baseline International Index of Erectile Function-6 (IIEF-6) score of

26 with immediate (dashed line) versus surgery delayed by 5 yr

(solid line).

Table 2

–

Difference in mean International Index of Erectile Function-6 (IIEF-6) score over a 10-yr or 15-yr time frame after prostate cancer

diagnosis (comparing immediate radical prostatectomy to 3-yr and 5-yr delays in surgery)

Age at diagnosis (yr)

RP delay (yr)

Time frame (yr)

Difference in mean IIEF-6 score

95% CI for difference

55

3

10

1.5

0.2, 3.0

15

1.0

–

0.2, 2.8

5

10

2.1

0.4, 3.9

15

1.3

–

0.5, 3.3

60

3

10

0.8

–

0.6, 1.8

15

0.2

–

1.3, 1.3

5

10

1.9

0.3, 3.1

15

0.8

–

0.9, 2.1

65

3

10

1.9

0.9, 3.0

15

1.3

0.1, 2.4

5

10

3.3

1.8, 4.6

15

2.2

0.4, 3.6

CI = con

fi

dence interval; RP = radical prostatectomy.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O GY 7 3 ( 2 0 18 ) 3 3

–

3 7

36