co-occurred, while

FH/TERT

(

p

= 0.04) were mutually

exclusive.

3.3.

Comparison to the TCGA data set

Fig. 5highlights differences in GA frequency in our data set

and the TCGA cohort. In both type 1 and type 2 disease, the

frequency of

MET

alterations (short variant mutations and

amplifications) is higher in our cohort (33% vs 17% for type

1; 7% vs 2% for type 2). By contrast,

MET

fusions were not

detected in this series but were observed in 1.3% of type

1 and 1.7% of type 2 cases in the TCGA cohort.

Similarly, alterations in

CDKN2A/B, FH

,

NF2

, and

SMARCB1

were identified more frequently in our data set. By contrast,

TCGA reported a higher frequency of alterations in

MLL2

and

SETD2

in type 2 disease.

4.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study reflects the largest

effort focused on genomic profiling of PRCC in a population

with more advanced disease. Our population is also slightly

larger than the TCGA PRCC cohort and includes a very

distinct stage distribution

[1]. In contrast to the 3% of

patients with confirmed stage IV disease noted in the TCGA

cohort, 60% of patients in our cohort had stage IV disease.

Furthermore, many patients had locally advanced (stage III)

PRCC (21%), and only a small minority (5%) had no

assignment of stage. It is possible that the more advanced

stage for patients in our cohort led to the marked

discordance in genomic findings highlighted in

Fig. 5, with

higher frequencies of alterations in

MET

,

CDKN2A/B

,

FH

, and

multiple SWI/SNF pathway elements. One caveat is that the

TCGA study also evaluated low-level copy gains for

chromosome 7 (including single copy gains) in their

analysis of

MET

alterations, and our comparative analysis

was limited to high-level amplifications, which may be a

more robust biomarker for responses to MET inhibitors on

the basis of studies in lung cancer

[18].

The findings of this study have potential therapeutic

implications, especially given the preponderance of ad-

vanced disease in this cohort. The higher frequency of

alterations in

MET

than previously recognized supports the

ongoing efforts to explore MET antagonists in prospective

clinical trials. Furthermore, cases with

MET

alterations with

concurrent

EGFR

or

KRAS

GAs should be carefully evaluated

for response to MET inhibitors, since it has been shown that

EGFR/KRAS

alterations mediate resistance to MET inhibition

[19,20], although a patient with carcinoma of unknown

primary harboring

MET

amplification and

KRAS

GAs

responded to crizotinib

[21].

The dual VEGFR2/MET inhibitor foretinib has shown

impressive activity in metastatic PRCC, with PFS of 9.3 mo

and a particularly high response rate (50%) among patients

with germline

MET

mutation

[22]. Results from the EORTC

CREATE trial assessing crizotinib showed a similar response

rate of 50% among patients with type 1 PRCC and

MET

mutation

[23]. Data from a phase 2 study of savolitinib, a

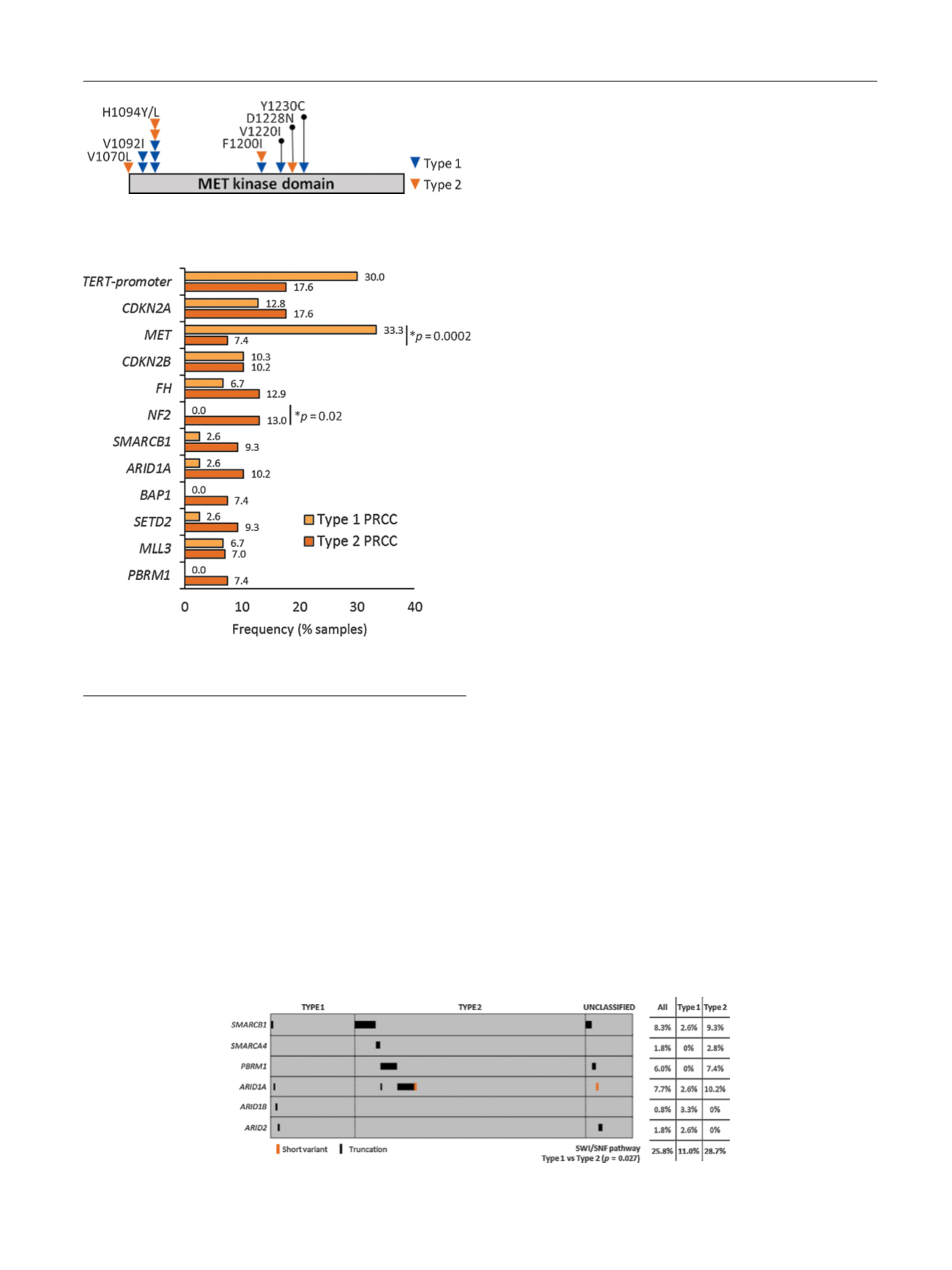

[(Fig._2)TD$FIG]

Fig. 2 – Sites of alteration in the

MET

protooncogene in patients with

type 1 and 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma.

[(Fig._3)TD$FIG]

Fig. 3 – Frequency of selected alterations in type 1 versus type

2 papillary renal cell carcinoma (PRCC).

[(Fig._4)TD$FIG]

Fig. 4 – SWI/SNF pathway analysis in type 1, type 2, and unclassified papillary renal cell carcinoma.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 3 ( 2 0 1 8 ) 7 1 – 7 8

75