more potent and selective MET inhibitor, were recently

presented

[24]. The study included 109 patients with

metastatic PRCC; PFS was significantly longer in patients

with

MET

alterations (6.2 vs 1.4 mo;

p

= 0.002).

The ongoing SWOG 1500 trial (NCT02761057) compares

the conventional strategy of VEGF inhibition with sunitinib

to MET inhibition (with either crizotinib, savolitinib, or

cabozantinib) in an unselected population of PRCC patients.

Another study (SAVOIR) is exploring the activity of

savolitinib versus control sunitinib in patients with MET-

driven PRCC (NCT03091192). Detailed efforts to character-

ize

MET

mutational status and copy number alterations

(CNAs) will accompany this effort. As diverse mechanisms

underlying

MET

dysregulation have now described, includ-

ing MET splice variants and intronic mutations

[25,26], it is

important to recognize what analyses were performed, as

the absence of alterations in CGP is not synonymous with

lack of an altered MET pathway.

Beyond

MET

, our data point towards other alterations

with potential therapeutic relevance. The cumulative

incidence of

CDKN2A/B

alterations was far higher in our

data set compared to the TCGA. CDK4/6 inhibitors may be

effective in patients with alterations in

CDKN2A

[27,28]. More than a quarter of our cohort also had

alterations along the SWI/SNF pathway. Kim et al

[29]demonstrated a dependence of SWI/SNF-mutated cancer

cell lines on EZH2-mediated stabilization of the PRC2

complex. Recent evidence also points towards the potential

efficacy of emerging EZH2 inhibitors in preclinical models

with SWI/SNF pathway alteration

[30,31]. The GAs seen in

the current series also point to patients predisposed to a

response to either VEGF- or mTOR-directed therapy. As one

example,

NF2

alterations were observed in 13% of the study

population; we have previously reported that this may

confer sensitivity to everolimus

[32]. In summary, the

alterations documented in our study could support (1) trials

exploring novel therapeutic targets (eg, MET, CDK4/6, or

EZH2) or (2) trials exploring mTOR- or VEGF-directed

agents in biomarker-selected populations with advanced

PRCC.

Our study also cites the mutational burden present in

PRCC, which is relatively low. There is an emerging

association between tumor burden and response to

immunotherapy in many tumor types; in RCC, these data

sets are relatively small

[33,34]. However, PD-1 inhibition

seems to have some encouraging activity in patients with

PRCC; understanding the correlation between tumor

burden and response in this unique cohort of patients

would be important

[35].

Other reports have offered genomic data for patients

with PRCC, but these data sets either focus on cohorts with

predominantly localized disease (eg, TCGA) or offer scant

details pertaining to clinical stage. For instance, Albiges and

colleagues

[36]reported genomic characterization of a large

PRCC cohort. In total, 220 specimens from patients with

PRCC were accessioned from the French RCC Network.

Notably absent, however, are data pertaining to clinical

stage in this cohort. Their findings are focused largely on

MET

expression and CNAs, both of which were elevated

among patients segregated by type 1 and type 2 disease.

Thus, the implications for MET inhibitors may be beyond

just MET mutations, and higher expression or MET CNAs

may constitute an MET-driven phenotype in the absence of

mutations.

Several limitations of our study should be acknowl-

edged. First, clinical outcomes data were not available for

the majority of patients in our series. However, for a select

number of patients, exceptional responses (derived from

therapies matched to genomic profile) have been docu-

mented. For instance, one patient harboring an alteration

in

MET

(H1094L) had a profound response to crizotinib

therapy

[37] .Prospective efforts such as the previously

described SWOG 1500 trial will hopefully validate such

observations. Second, we acknowledge that the majority

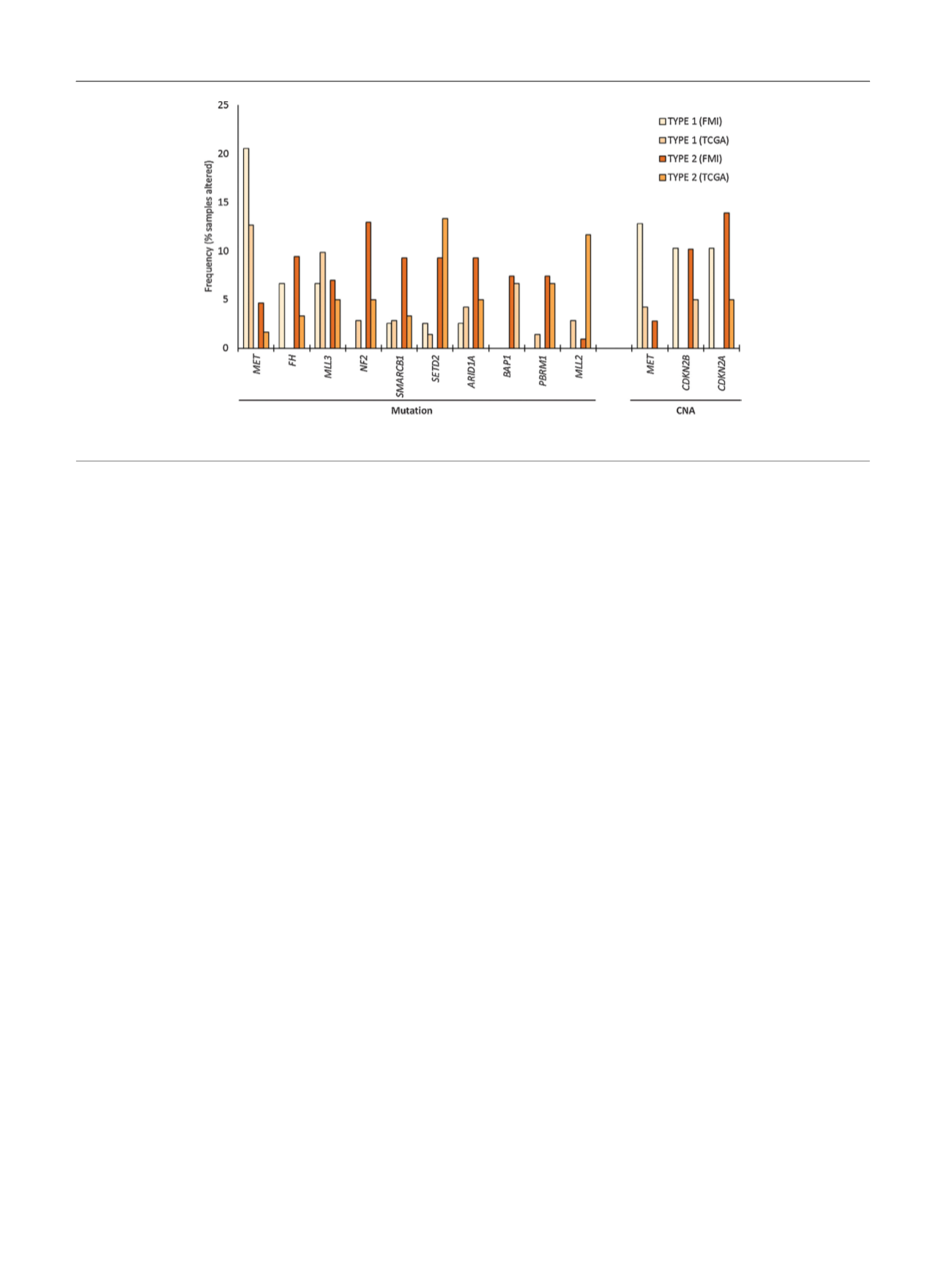

[(Fig._5)TD$FIG]

Fig. 5 – Frequency of genetic alterations in the current data set (FMI) versus The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). CNA = copy number alteration.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 3 ( 2 0 1 8 ) 7 1 – 7 8

76