The MRI characteristics are shown in

Table 3 .Six studies

used 3-T scanners, two used 1.5-T scanners, and two used

1.5- or 3-T scanners. Regarding coverage of MRI, four

studies used whole-body MRI, two assessed the axial

skeleton, and four covered only the pelvis using a routine

prostate MRI protocol. A combination of DWI and conven-

tional sequences (T1WI, T2WI, and/or STIR) was used in five

studies, only DWI in one study, and only conventional

sequences in four studies. The criteria for bone metastasis

were explicit in seven studies; however, three studies were

not clear on this issue as one study was not explicit

regarding the role of T1WI and STIR, another study did not

provide any criteria, and the other simply stated the use of a

five-point Likert scale.

3.3.

Quality assessment

Overall, the quality of the studies was considered moderate,

with eight of the 10 studies satisfying at least four of the

seven QUADAS-2 domains

( Fig. 2). Regarding the patient

selection domain, one study was considered to have a high

risk of bias due to a nonconsecutive case/control design

[[10_TD$DIFF]

19]. In addition, one study was considered to have an

unclear risk of bias, as it did not explicitly mention whether

patient enrollment was consecutive or not

[9] .There was

high concern for applicability in one study, as it included

patients with no metastasis or oligometastasis (

<

5 metas-

tases) based on conventional imaging and excluding those

with polimetastasis

[[6_TD$DIFF]

15]. Regarding the index test domain,

there was an unclear risk of bias in four studies, as it was

unclear whether MRI was evaluated blinded to the

reference standard in one study

[9]and whether a

prespecified threshold was used in three studies

[[23_TD$DIFF]

15,16,19] .There was low concern for applicability in all

10 studies. Regarding the reference standard domain, all the

studies had an unclear risk of bias, as it was unclear whether

the derivation of the reference standard was blinded to MRI.

There was unclear concern for applicability in three studies,

as they did not explicitly mention whether MRI–reference

standard interval was at least 6 mo when BVC was used as

the reference standard

[[24_TD$DIFF]

6,15,20]. Regarding the flow and

timing domain, three studies had a high risk of bias as

different reference standards were applied within the study

[[25_TD$DIFF]

4,6,16,19] .Two studies were considered to have an unclear

risk of bias as the MRI–reference standard interval was not

provided

[[26_TD$DIFF]

15,20].

3.4.

Diagnostic accuracy

The sensitivity and specificity of the 10 individual studies

were 72–100% and 70–100%, respectively. Although the

Cochran’s

Q

test suggested that heterogeneity was not

present (

Q

= 2.970,

p

= 0.113), the Higgins

I

2

[21_TD$DIFF]

statistics

demonstrated substantial heterogeneity with regard to

both sensitivity (

I

2

= 81.44%) and specificity (

I

2

= 85.85%).

No threshold effect was shown upon visualization of the

coupled forest plot of sensitivity and specificity

( Fig. 3), with

a correlation coefficient between sensitivity and false

positive rate of –0.581 (95% confidence interval [CI] –

0.886 to 0.077).

For all 10 studies combined, the pooled sensitivity and

specificity were 0.96 (95% CI 0.87–0.99) and 0.98 (95% CI

0.93–0.99), respectively. In the HSROC curve, there was a

large difference between the 95% confidence and prediction

regions, additionally indicating that heterogeneity was

present between the studies

( Fig. 4). The area under the

HSROC curve was 0.99 (95% CI 0.98–1.00). According to the

Deeks et al’s

[13]funnel plot, the likelihood of publication

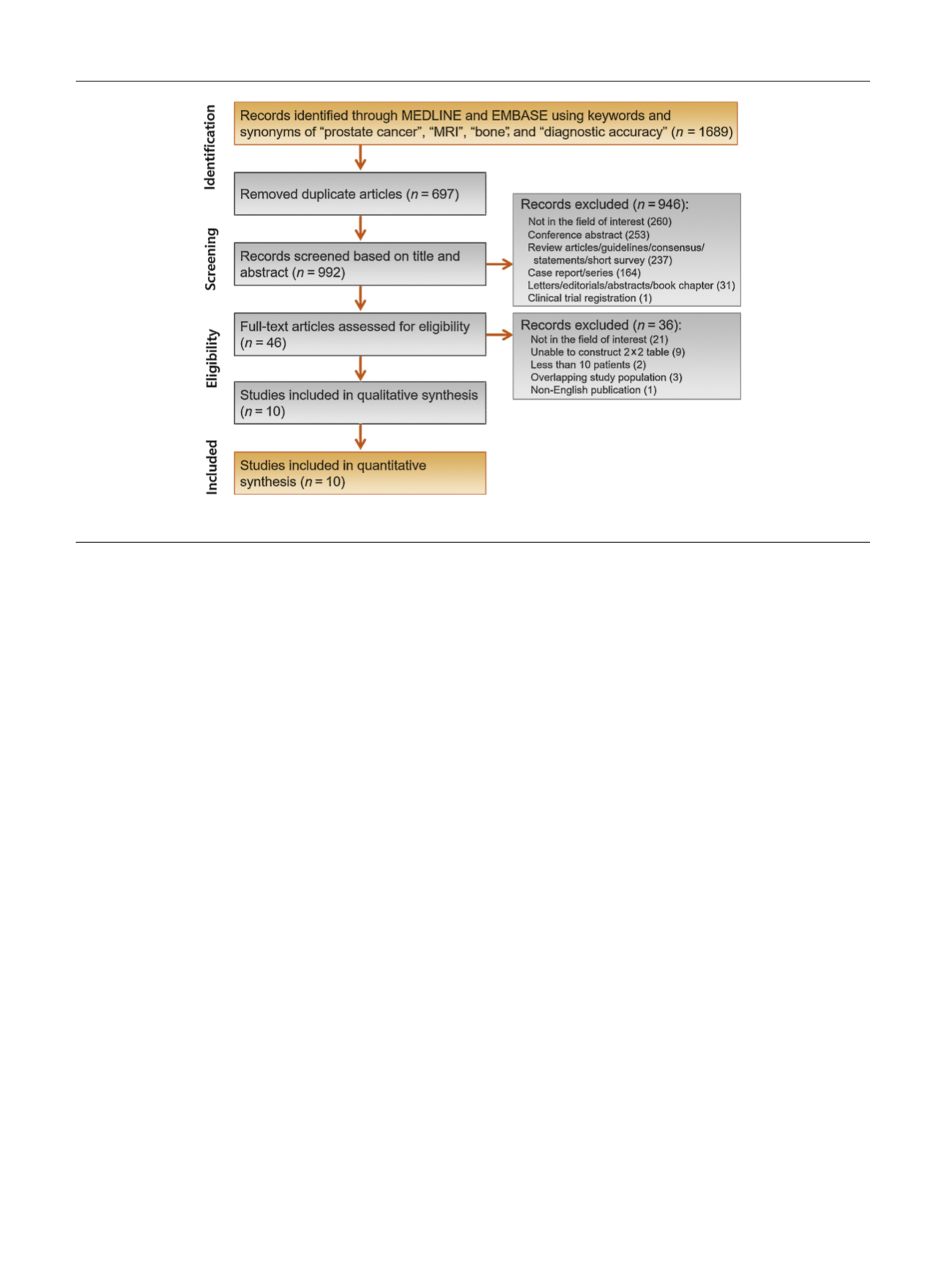

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1 – Flow diagram showing study selection process for meta-analysis. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 3 ( 2 0 1 8 ) 8 1 – 9 1

84