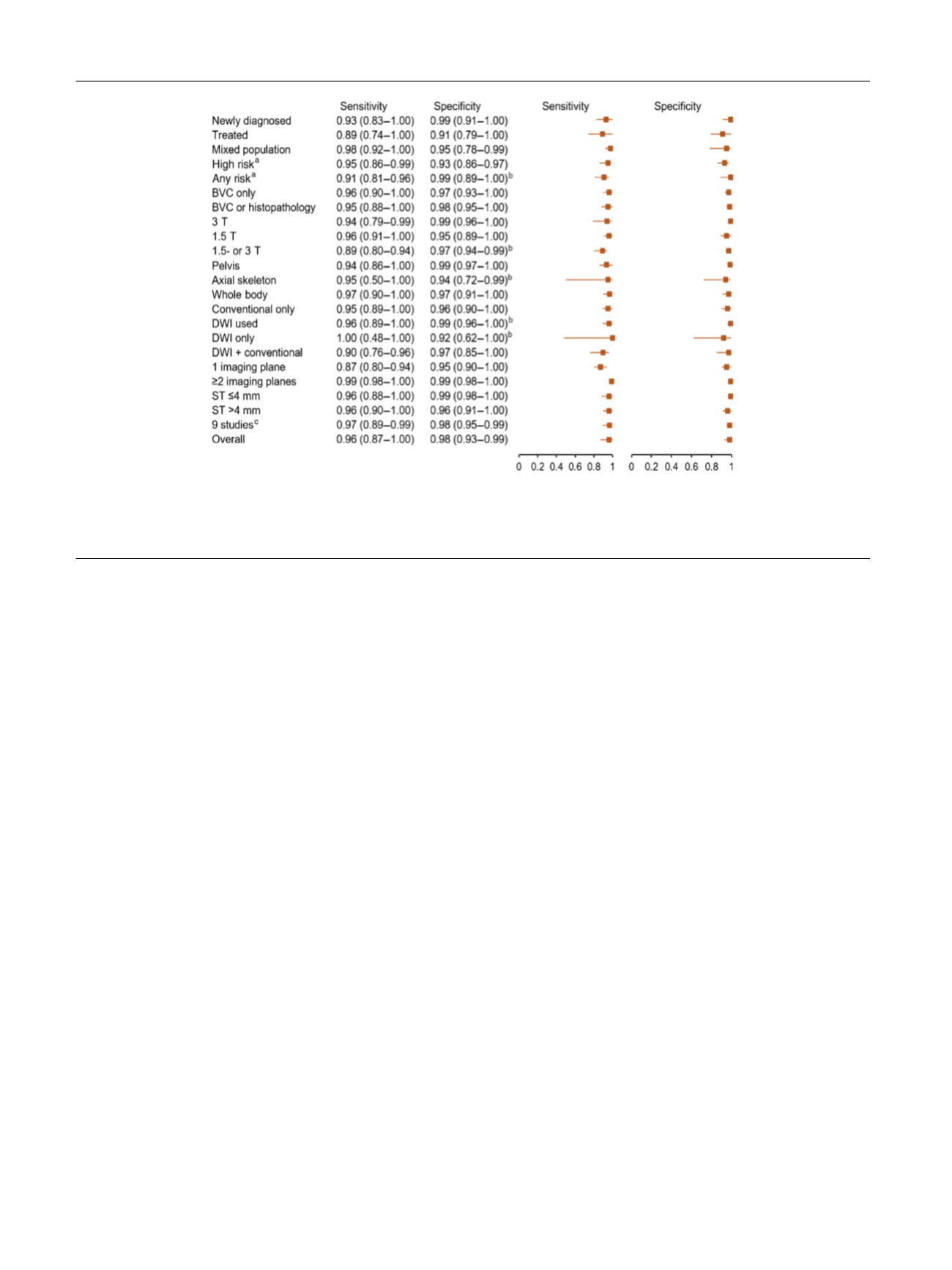

intermediate risk of bone metastasis only. Therefore, we

performed sensitivity analysis excluding this single study,

and yielded consistent diagnostic performance with a

substantially lower degree of heterogeneity: sensitivity

and specificity of 0.97 (95% CI 0.89–0.99) and 0.98 (95% CI

0.95–0.99), respectively;

I

2

= 57.4 and 75.64, respectively.

One of the major limitations of our meta-analysis is that all

included studies used BVC or predominantly BVC as the

reference standard. As BVC is based on a combination of

clinical, laboratory, imaging, and follow-up studies, this

inherently imposes a significant risk for differential verifica-

tion biases among all included patients. However, it is unlikely

that any further study will solely use biopsy or surgery to

obtain histopathological results for the reference standard

when determining bone metastasis, as this would not be

feasible in clinical practice and would be ethically unjustifi-

able. Another limitation of this meta-analysis is that we were

unable to assess the per-lesion diagnostic performance of

MRI, as only two studies provided such information. Future

studies may be needed to elucidate the per-lesion sensitivity

and specificity of MRI for the detection of bone metastasis in

patients with prostate cancer. Furthermore, caution is needed

in applying our results to routine clinical practice, as therewas

substantial heterogeneity among the included studies and we

used the results with the highest accuracy when diagnostic

performance from multiple independent readers were

provided in the included studies.

4.

Conclusions

MRI shows excellent sensitivity and specificity for the

detection of bone metastasis in patients with prostate

cancer. Studies using two or more planes for assessment

showed the highest sensitivity and specificity, while

diagnostic performance was consistently high across

multiple subgroups.

Author contributions:

Sang Youn Kim had full access to all the data in the

study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design:

Woo, Suh, S.Y. Kim.

Acquisition of data:

Woo, Suh, S.Y. Kim.

Analysis and interpretation of data:

Woo, Suh, S.Y. Kim.

Drafting of the manuscript:

Woo.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content:

Suh,

S.Y. Kim, Cho, S.H. Kim.

Statistical analysis:

Suh.

Obtaining funding:

None.

Administrative, technical, or material support:

None.

Supervision:

S.Y. Kim, Cho, S.H. Kim.

Other:

None.

Financial disclosures:

Sang Youn Kim certifies that all conflicts of

interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and

affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the

manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultan-

cies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties,

or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor:

None.

References

[1]

Carlin BI, Andriole GL. The natural history, skeletal complications, and management of bone metastases in patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2000;88:2989–94.[2]

Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol 2017;71:618–29.[(Fig._6)TD$FIG]

Fig. 6 – Forest plots of sensitivity analyses showing pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates and corresponding 95% CIs for various subgroups.

BVC = best value comparator; CI = confidence interval; DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging; ST = slice thickness.

a

Risk of bone metastasis based on

clinical criteria (Gleason grade, clinical T stage, prostate-specific antigen, or prostate-specific antigen doubling time).

b

Unstable pooled estimates (<3

studies).

c

Excluding study by Conde-Moreno et al

[15].

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 3 ( 2 0 1 8 ) 8 1 – 9 1

90