angiogenesis (hypoxia inducible factor 1

a

and metallopro-

teinases), cell proliferation (Ki-67), epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (Snail), mitosis (Aurora A), apoptosis (Bcl-2 and

survivin), vascular invasion (RON), and c-met protein (MET)

[1,29,47] .Microsatellite instability (MSI) is an independent

molecular prognostic marker

[48]. MSI can help detect

germline mutations and hereditary cancers

[10]. Because of

the rarity of UTUC, the main limitations of the above studies

are their retrospective design and small sample size. None of

the markers have fulfilled the criteria necessary to support

their introduction in daily clinical decision making.

3.4.3.

Predictive tools

Accurate predictive tools are rare for UTUC. There are two

models in the preoperative setting: one for predicting LND

of locally advanced cancer that could guide the decision to

perform, or not, an LND as well as the extent of LND at the

time of RNU

[1] ,and one for the selection of non

–

organ-

confined UTUC that is likely to benefit from RNU

[49]. Four

nomograms are available predicting survival rates postop-

eratively, based on standard pathological features

[1,50,51].

3.4.4.

Bladder recurrence

A recent meta-analysis of available data has identified

significant predictors of bladder recurrence after RNU

[52](LE: 3). Three categories of predictors of increased risk for

bladder recurrence were identified:

1. Patient-specific factors such as male gender, previous

BCa, smoking and preoperative chronic kidney disease

2. Tumour-specific factors such as positive preoperative

urinary cytology, ureteral location, multifocality, invasive

pT stage, and necrosis

3. Treatment-specific factors such as laparoscopic ap-

proach, extravesical bladder cuff removal, and positive

surgical margins

[52]In addition, the use of diagnostic ureteroscopy has been

associated with a higher risk of developing bladder

recurrence after RNU

[53](LE: 3).

3.4.5.

Risk stratification

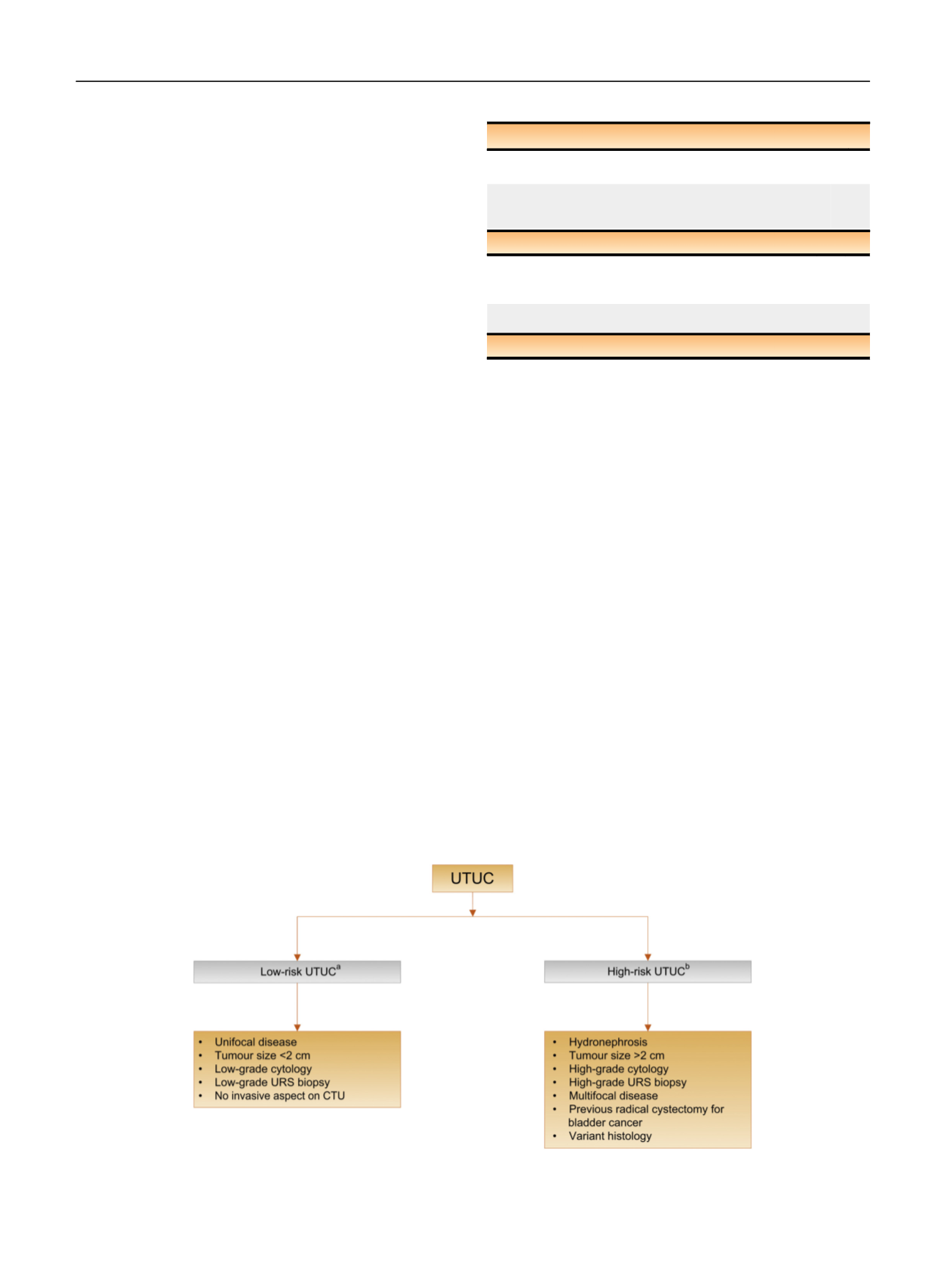

As tumour stage is difficult to assert clinically in UTUC, it is

useful to

“

risk stratify

”

UTUC between low- and high-risk

tumours to identify those who are more suitable for kidney-

sparing treatment rather than radical extirpative surgery

[1] ( Fig. 3).

3.5.

Disease management

3.5.1.

Localised disease

3.5.1.1. Kidney-sparing surgery.

Kidney-sparing surgery (KSS) for

low-risk UTUC allows sparing the morbidity associated with

radical surgery, without compromising oncological out-

comes and kidney function

( Table 3 ) [1] .In low-risk cancers,

it is the preferred approach with survival being similar after

KSS versus RNU

[54] .This option should therefore be

discussed in all low-risk cases, irrespective of the status of

the contralateral kidney. In addition, it can also be

considered in select patients with serious renal insufficiency

or solitary kidney (LE: 3). Recommendations for kidney-

sparing management of UTUC are listed in

Table 4.

3.5.1.1.1. Ureteroscopy.

Endoscopic ablation can be considered

in patients with clinically low-risk cancer in the following

situations

[1,55]:

Table 3

–

Summary of evidence and guidelines for prognosis

Summary of evidence

LE

Age, sex, and ethnicity are no longer considered as independent

prognostic factors.

3

Primary recognised postoperative prognostic factors are tumour

stage and grade, extranodal extension, and lymphovascular

invasion.

3

Recommendations

LE GR

Use microsatellite instability as an independent molecular

prognostic marker to help detect germline mutations

and hereditary cancers.

3 C

Use the American Society of Anesthesiologists score to assess

cancer-speci

fi

c survival following surgery.

3 C

GR = grade of recommendations; LE = level of evidence.

[(Fig._3)TD$FIG]

Fig. 3

–

Risk stratification of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. CTU = computed tomography urography; URS = ureteroscopy; UTUC = upper

urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

a

All these factors need to be present.

b

Any of these factors need to be present.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O GY 7 3 ( 2 0 18 ) 111

–

1 2 2

116