discouraged, but the G8 seems the most robust

[55]. Pro-

spective studies evaluating the impact of using GAs on the

decision-making process are needed.

Not only OS but also CSS after RC is worse for older

patients, implying that age alone is not responsible for

worse outcome.

Besides differences in health status, a poorer outcome in

elderly patients might be explained by the observation that

these patients often receive a suboptimal

curative

treat-

ment. This, despite compelling evidence that, even in

patients aged 80 yr, an aggressive approach improves

survival

[56] .There is Level 1 evidence that neoadjuvant

chemotherapy improves survival significantly

[57]. Poor

performance status and impaired kidney function in elderly

are contraindications for platinum-based chemotherapy

and can discourage physicians to use perioperative chemo-

therapy

[15,16,58,59]or lead to dosage reduction

[60]. Data

do, however, indicate that neoadjuvant chemotherapy can

be administrated safely and with comparable clinical

outcome to patients aged

<

70 yr in appropriately selected

elderly patients

[61]. Information of administration of

perioperative chemotherapy in the selected articles was

limited.

Although it is recommended to perform a RC with a

pelvic lymph node dissection, the place of an extended

lymph node dissection remains debatable, particularly in

elderly patients

[62]. Nevertheless, several articles have

suggested a correlation between extent of pelvic lymph

node dissection and outcome

[63,64], in both patients aged

<

80 yr and octogenarians

[58] .In practice, an extended

pelvic lymph node dissection is often omitted in elderly

patients in order to limit operative time and reduce the risk

of postsurgical complications

[15,58].

Also, the type of urinary diversion differs between age

groups. Therefore, will older patients more likely receive

incontinent urinary diversions such as an ileal conduit

(6,16,27,34–36,42,45). Whether the type of diversion on its

own has a major impact on clinical outcome is doubtful

[35,65]. However, this could suggest that elderly patients are

diagnosed at more advanced stages

[8,16,21]as patients

with advanced clinical stage are more likely to receive

incontinent urinary diversions

[44]. Only eight articles

included in this systematic review reported the tumor stage

per age group. Four articles reported more advanced tumor

stage at presentation in elderly patients with inferior CSS

and/or OS for elderly patients in three of them

[8,16,27]. Four

articles

[6,11,18,37]did not found differences in stage

distribution between younger and older patients. Similar OS

between both groups was reported in two of them

[6,18]. In

contrast to OS, CSS was not worse for elderly patients in the

publication of Guillotreau et al

[11]. With similar tumor

stage at presentation the complication rate appears compa-

rable between younger and older patients

[37].

A major concern when treating older patients with

radical cystectomy is POM. Good patient evaluation is

crucial to improve patient survival. Not surprisingly, older

patients have a poorer American Society of Anaesthesiol-

ogists physical status classification

[66]. Despite improve-

ments in perioperative care resulting in a significant

reduction of POM, POM remains more prevalent in

septuagenarians with a 2- to 6-fold increased risk compared

with patients

<

70 yr old. Perioperative mortality has

decreased significantly with time in high-volume and

moderate-volume centres pointing out the importance of

referring patients, certainly those who are most vulnerable

of dying from the procedure, to those centres

[17].

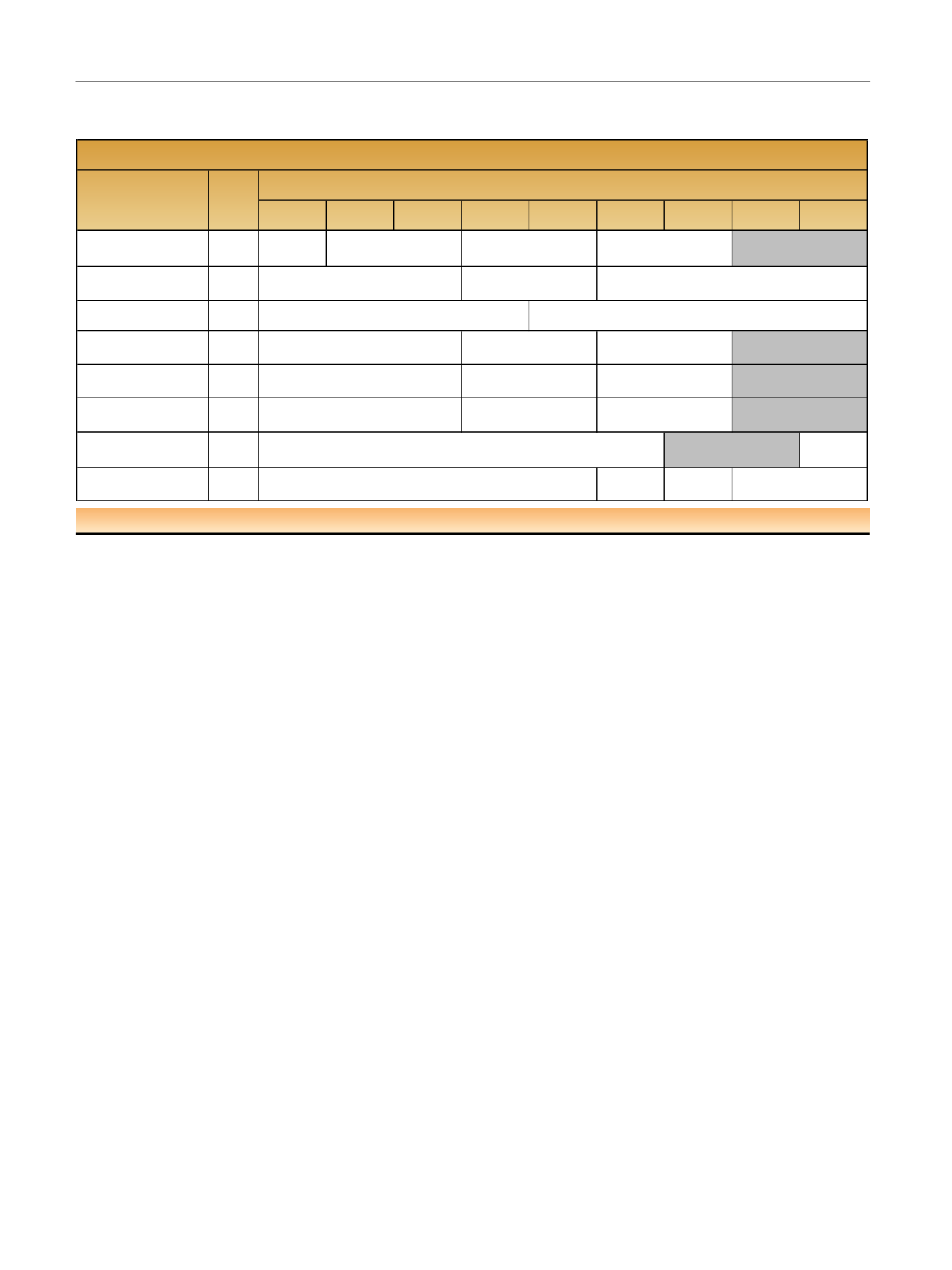

Table 4 – Multivariate analysis evaluating impact of age on cancer specific survival rates per age group and per study. The studies in grey

represent the studies where a significant difference was observed between younger and older patients

50

–

54

<50

55

–

59

60

–

64

65

–

69

70

–

74

75

–

79

80

–

84

≥85

Chromecki et al [21] 2012

ref (

N

= 321)

4429

Dalbagni et al [19] 2001

297

Dotan et al [31] 2007

1586

Fairey et al [16] 2012

2263

Patel et al [17] 2015

804

Nielsen et al [28] 2007

888

Morgan et al [23] 2012

3170

1.32 (95%

CI:0.91

-

Leveridge et al [15] 2015

ref (

N

= 582)

1701

1.02(95%

CI:0.93

-

1.26)

0.87(95%CI:0.68

-

1.13)

(

N

= 846)

ref (

N

= 1613)

1.24(95%CI:1.05

-

1.46,

p

= 0.009) (

N

= 1406)

NR

1.02 (95%CI:0.87

-

1.19,

p

= 0.522) (

N

= 578)

ref (

N

= 150)

1.24 (95%CI:0.86

-

1.80)

(

N

= 245)

1.36(95%CI:0.96

-

1.90)

(

N

= 339)

2.54(95%CI:1.62

-

3.96)

(

N

= 70)

ref (

N

= 240)

1.226 (0.884

-

1.700,

p

= 0.222) (

N

=331)

1.296(95%CI:0.921

-

1.823,

p

= 0.136) (

N

= 266)

1.742(1.015

-

2.990,

p

= 0.044) (

N

= 51)

1.56 (95%CI:1.09

-

2.24)

(

N

= 181)

ref (

N

= 557)

0.96 (95%CI:0.74

-

1.26)

(

N

= 679)

Cancer specific survival

N

Author

Trials with radical cystectomy

0.795 (95%CI:0.610

-

1.044,

p

= 0.1)(

N

= 815)

0.979 (95%CI:0.766

-

1.252,

p

= 1.252) (

N

= 1595)

1.128 (95%CI:0.880

-

1.446,

p

≤ 0.341)

1.763 (95%CI:1.238

-

2.424,

p

< 0.001) (

N

= 275)

ref (

N

= 73)

1.137 (95%CI:0.605

-

2.137,

p

= 0.6890) (

N

= 106)

1.117 (95%CI:0.619

-

2.017,

p

= 0.7135) (

N

= 118)

ref (

N

= 613)

1.26 (95%CI:0.91

-

2.017,

p

= 0.14) (

N

= 973)

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; NR = not reported; Ref = reference.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 3 ( 2 0 1 8 ) 4 0 – 5 0

46